Wednesday, November 30, 2005

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

Monday, November 28, 2005

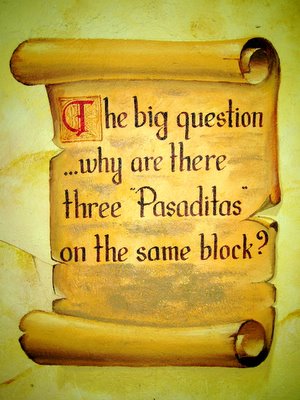

Quotation Marks

Check out the use of quotation marks on the sign above.

I've long wanted to collect examples of the great variety of uses quotation marks are put to in public signs. Please submit examples. My hope is that as we collect examples, patterns will emerge and we can begin to understand why they are used to mark something other than the fact that someone is being quoted or that the enclosed word(s) are being mentioned, not used. Here's an example of such a deviant use of quotation marks that only began to make sense to me once I had others to compare it to:

A "No Smoking" sign in a restaurant. I feel like this is like "Pay Before Pumping" signs I've seen at gas stations. In these cases, I feel like the quotation marks are letting you know that someone is ordering you to do (or not do) something. They're "command marks", one could say.

So what are the quotation marks in the sign above doing?

Friday, November 18, 2005

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Dorm Room Debates

Michael G. just suggested to me a useful criterion for judging the value of an undergraduate philosophy course: whether it gives its students the ability to step in and either arbitrate or dissolve common undergraduate dorm room debates, such as debates about whether everything we do is out of self-interest, or whether everything is relative, or whether we have free will, etc

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Apparent Distinctions Worth Preserving

Distinctions:

A) Disagreements about belief vs. Disagreements about meaning

B) Disagreements about belief vs. Ethical disagreements

Illuminating similarities between the philosophical debates that have arisen in regard to these distinctions:

Debate A: Quine vs. Carnap

i) Quine: denies that there’s anything distinctive about disagreements about meaning, and thereby reduces disagreements about meaning to disagreements about belief

ii) Carnap: in order to preserve the distinction, reduces disagreements about meaning to non-cognitive disputes

iii) Kuhn: in attempting to preserve the distinction while not reducing disagreements about meaning to non-cognitive disputes runs the risk of making a mystery of how genuine disagreements about meaning are so much as possible (Kitcher’s point)

iv) Travis: there are no meanings, but there are shared ways of understanding contextual factors

Debate B: McDowell vs. Blackburn

i) McDowell: denies that there’s anything distinctive about ethical disagreements, and thereby reduces ethical disagreements to disagreements about belief

ii) Blackburn: in order to preserve the distinction, reduces ethical disagreements to non-cognitive disputes

iii) McDowell: in an attempt to preserve a sense that there’s something distinctive about thick ethical concepts while neither assimilating their use to the use of ordinary empirical concepts nor reducing what’s distinctive about them to a separable non-cognitive element, runs the risk of making a mystery of how genuine ethical disagreements which utilize thick ethical concepts are so much as possible (Blackburn’s point)

iv) ?

Question

Disagreements about meaning are settled, for the late Kuhn, by choices of packages of meanings. Such choices, however, are guided by how the world is, or, at minimum, by the recognition of how the world is not (i.e., by the recognition that a particular package is falsified by how the world actually is). Is there anything analogous to such a form of choice in regard to ethical disagreement?

A) Disagreements about belief vs. Disagreements about meaning

B) Disagreements about belief vs. Ethical disagreements

Illuminating similarities between the philosophical debates that have arisen in regard to these distinctions:

Debate A: Quine vs. Carnap

i) Quine: denies that there’s anything distinctive about disagreements about meaning, and thereby reduces disagreements about meaning to disagreements about belief

ii) Carnap: in order to preserve the distinction, reduces disagreements about meaning to non-cognitive disputes

iii) Kuhn: in attempting to preserve the distinction while not reducing disagreements about meaning to non-cognitive disputes runs the risk of making a mystery of how genuine disagreements about meaning are so much as possible (Kitcher’s point)

iv) Travis: there are no meanings, but there are shared ways of understanding contextual factors

Debate B: McDowell vs. Blackburn

i) McDowell: denies that there’s anything distinctive about ethical disagreements, and thereby reduces ethical disagreements to disagreements about belief

ii) Blackburn: in order to preserve the distinction, reduces ethical disagreements to non-cognitive disputes

iii) McDowell: in an attempt to preserve a sense that there’s something distinctive about thick ethical concepts while neither assimilating their use to the use of ordinary empirical concepts nor reducing what’s distinctive about them to a separable non-cognitive element, runs the risk of making a mystery of how genuine ethical disagreements which utilize thick ethical concepts are so much as possible (Blackburn’s point)

iv) ?

Question

Disagreements about meaning are settled, for the late Kuhn, by choices of packages of meanings. Such choices, however, are guided by how the world is, or, at minimum, by the recognition of how the world is not (i.e., by the recognition that a particular package is falsified by how the world actually is). Is there anything analogous to such a form of choice in regard to ethical disagreement?

Counter-exampled

Just thought of a counter-example to my new brand of moral anti-realism (outlined in a previous post). Consider the following imaginary case:

Gustaf arrives early to coffee hour, before anyone else. He finds that there is only one package of Choco Leibniz. Although he has just finished a late lunch at Harold's Chicken Shack, which has left him stuffed, he proceeds to eat the entire package, knowing full well that others would have liked some.

I think a perfectly respectable explanation for Gustaf's action is that he is greedy. And I think that greediness is a moral property. Now imagine that neither Gustaf, nor anyone else, think that Gustaf is greedy. We then have an example of an instantiation of a moral property, one that no one thinks anything about, figuring ineliminably in a perfectly respectable causal explanation. Which is a counter-example to my new brand of moral anti-realism.

I have two things to say about this counter-example:

(1) It doens't undermine my proposal for distinguishing realism from anti-realism, it just implies that we should account for (certain) moral properties/facts in realist terms. Meaningfulness may still fall on the anti-realist side of things.

(2) I still think there's something right about the thought that it's unreasonable to be consoled by the existence of moral facts that no one thinks anything about. Maybe I just need a new way to articulate why I think this is unreasonable.

Gustaf arrives early to coffee hour, before anyone else. He finds that there is only one package of Choco Leibniz. Although he has just finished a late lunch at Harold's Chicken Shack, which has left him stuffed, he proceeds to eat the entire package, knowing full well that others would have liked some.

I think a perfectly respectable explanation for Gustaf's action is that he is greedy. And I think that greediness is a moral property. Now imagine that neither Gustaf, nor anyone else, think that Gustaf is greedy. We then have an example of an instantiation of a moral property, one that no one thinks anything about, figuring ineliminably in a perfectly respectable causal explanation. Which is a counter-example to my new brand of moral anti-realism.

I have two things to say about this counter-example:

(1) It doens't undermine my proposal for distinguishing realism from anti-realism, it just implies that we should account for (certain) moral properties/facts in realist terms. Meaningfulness may still fall on the anti-realist side of things.

(2) I still think there's something right about the thought that it's unreasonable to be consoled by the existence of moral facts that no one thinks anything about. Maybe I just need a new way to articulate why I think this is unreasonable.

Monday, November 14, 2005

Sunday, November 13, 2005

Is Turing's Intuition Pump Broken?

Google is getting to be amazingly effective at answering questions, and that fact makes me think the best response to the Turing test may simply be to deny that we would intuitively think that the reasonable responses coming back over the teletype must be produced by a thinking thing. I mean, Google's effectiveness is often incredible, but I'm not inclined, at all, to think it's intelligent, conscious, or whatever.

Saturday, November 12, 2005

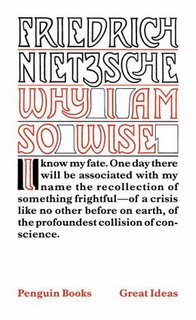

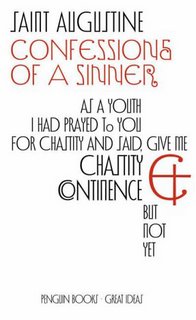

Best Book Covers

I originally wanted to title this post "Worst Book Covers", but then I decided that it wouldn't be very nice to pick on the graphic design problems that plagued the philosophy series of certain American publishers in the late 1990s. If you're in the mood for making such a list, I encourage you to submit your suggestions in the comments section below. Or, if you're that type of (negative) person, you might simply rest content with enjoying the "Worst Album Covers" lists currently circulating the internet, such as the one at the following website:

http://porktornado.diaryland.com/albumcover.html

Anyway, in an attempt to be a positive sort of guy, I nominate Penguin's "Great Ideas" series as the best book covers of 2005. I've posted a couple of their philosophy titles above, which contain selections from Nietzsche and Augustine, respectively. To be honest, however, these books must be seen in person to be fully appreciated, because the designs on the covers are embossed. The gist of the cover design of the series is that each cover aims to emulate the sort of typography (or calligraphy) that is characteristic of the age in which the text was originally written. The full series can be enjoyed at the following website:

http://www.penguin.co.uk/static/cs/uk/0/articles/greatideas/

Friday, November 11, 2005

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

Want List

Among record collectors it is common practice to put together a want list of records you've been looking for but can't find, and to distribute this list to other collectors and dealers. Don't know why, but I never before thought of doing this with philosophy articles. Check out the following list:

http://www.helsinki.fi/~tuschano/wants/articles/

I'm going to have to start putting together my own such list. I encourage others to submit ones as well.

http://www.helsinki.fi/~tuschano/wants/articles/

I'm going to have to start putting together my own such list. I encourage others to submit ones as well.

(Yet Another) Philosophical Illusion

Although I think philosophy would benefit from a decreased interest in rooting out the illusions that grip others, and an increased interest in merely rooting out falsity, I thought I would share a recent thought I've had about (what I take to be) a particularly clear instance of a philosophical illusion.

This past summer, while teaching a philosophy of mind class, I was discussing the putative possibility of an inverted spectrum and was trying to explain to the students what it means to say, as advocates of this possibility usually say, that someone for whom the color wheel is inverted would be “behavioristically indistinguishable” from someone for whom it is not inverted. (This is, of course, why the putative possibility of an inverted spectrum is supposed to be so devastating for accounts of mind that posit a necessary connection between mental experience and behavior.) As a means of working towards an understanding of what it would be for something to be a subjective mental difference that is behavioristically indistinguishable, I asked them to give me an example of a subjective mental difference that is behavioristically distinguishable. This query immediately derailed the intended trajectory of my discussion and led several of them to start talking about how we can (according to them) explain differences in people’s preferences (as expressed in their behavior) by positing differences in how things look, taste, smell, etc., for them.

The first thing to say about such comments is that our tendency to say such things is almost overwhelming. I think almost everyone is tempted to think that such subjective mental differences can explain differences in our overt behavior. And I don’t think there’s anything, as such, wrong with invoking such differences. For example, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with explaining why someone likes the taste of Coke, but despises Pepsi, by saying ‘Well, Coke tastes good to her but Pepsi doesn’t’.

But I do think that there’s enormous potential for illusion in such comments, and it’s this potential for illusion that I want to focus on. The illusion arises out of the tendency to think that by invoking differences in how things look, taste, smell, etc., we’ve somehow explained why some people are drawn to certain things, and others aren’t, without relying upon the notion of preference. The illusory thought is that by saying ‘Well, she likes Coke, and you don’t, because it tastes different to her’ we’re explaining why she is drawn to it—the illusion is that we’ve eliminated her role in her behavior, as it were, and found something that just anyone would be drawn to, if that’s how things looked, tasted, smelt, etc., to them. But if there is a question about why she prefers Coke, then I can’t, for the life of me, see why there shouldn’t equally well be a question about why she prefers that taste (i.e., the taste that is being posited as a taste that just anyone would be drawn to). The problem is that if there’s a question about why people prefer the external objective things they prefer, then there’s equally well a question about why people prefer the internal subjective things they prefer. And to think otherwise—i.e., to think that by positing subjective mental differences we’re leaving this question behind—is sheer illusion.

That, I think, is a clear case of a philosophical illusion. For an example of an illusion that is probably a little more interesting, check out the following link:

http://www.michaelbach.de/ot/mot_mib/index.html

For a useful discussion of why the putative possibility of an inverted spectrum is an illusion, check out the following link:

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qualia-inverted/

This past summer, while teaching a philosophy of mind class, I was discussing the putative possibility of an inverted spectrum and was trying to explain to the students what it means to say, as advocates of this possibility usually say, that someone for whom the color wheel is inverted would be “behavioristically indistinguishable” from someone for whom it is not inverted. (This is, of course, why the putative possibility of an inverted spectrum is supposed to be so devastating for accounts of mind that posit a necessary connection between mental experience and behavior.) As a means of working towards an understanding of what it would be for something to be a subjective mental difference that is behavioristically indistinguishable, I asked them to give me an example of a subjective mental difference that is behavioristically distinguishable. This query immediately derailed the intended trajectory of my discussion and led several of them to start talking about how we can (according to them) explain differences in people’s preferences (as expressed in their behavior) by positing differences in how things look, taste, smell, etc., for them.

The first thing to say about such comments is that our tendency to say such things is almost overwhelming. I think almost everyone is tempted to think that such subjective mental differences can explain differences in our overt behavior. And I don’t think there’s anything, as such, wrong with invoking such differences. For example, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with explaining why someone likes the taste of Coke, but despises Pepsi, by saying ‘Well, Coke tastes good to her but Pepsi doesn’t’.

But I do think that there’s enormous potential for illusion in such comments, and it’s this potential for illusion that I want to focus on. The illusion arises out of the tendency to think that by invoking differences in how things look, taste, smell, etc., we’ve somehow explained why some people are drawn to certain things, and others aren’t, without relying upon the notion of preference. The illusory thought is that by saying ‘Well, she likes Coke, and you don’t, because it tastes different to her’ we’re explaining why she is drawn to it—the illusion is that we’ve eliminated her role in her behavior, as it were, and found something that just anyone would be drawn to, if that’s how things looked, tasted, smelt, etc., to them. But if there is a question about why she prefers Coke, then I can’t, for the life of me, see why there shouldn’t equally well be a question about why she prefers that taste (i.e., the taste that is being posited as a taste that just anyone would be drawn to). The problem is that if there’s a question about why people prefer the external objective things they prefer, then there’s equally well a question about why people prefer the internal subjective things they prefer. And to think otherwise—i.e., to think that by positing subjective mental differences we’re leaving this question behind—is sheer illusion.

That, I think, is a clear case of a philosophical illusion. For an example of an illusion that is probably a little more interesting, check out the following link:

http://www.michaelbach.de/ot/mot_mib/index.html

For a useful discussion of why the putative possibility of an inverted spectrum is an illusion, check out the following link:

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qualia-inverted/

Sunday, November 06, 2005

Blackburn Review of Anscombe

I highly recommend the following review by Simon Blackburn of a new collection of essays by GEM Anscombe titled 'Human Life, Action and Ethics'.

http://www.phil.cam.ac.uk/~swb24/reviews/Anscombe.htm

I think I agree with everything he says in it. Consider that an open invitation to argue with me about it.

http://www.phil.cam.ac.uk/~swb24/reviews/Anscombe.htm

I think I agree with everything he says in it. Consider that an open invitation to argue with me about it.

Friday, November 04, 2005

"I sit at the computer for most of the day, erasing what I wrote the day before."

Last night at a party, someone asked me if I am an economist. Last weekend at a party, someone asked me if I am a journalist. The weekend before that, I was asked if I am a lawyer. I still have no adequate way of describing to non-philosophy people what I actually do. So I'm tempted just to assent to whatever field it is assumed that I work in. As it is, I'll agree to almost anything someone says about philosophy, once I own up to working in it. Just to make people feel like they have some idea what I do. (Just to make myself feel like they have some idea what I do.) It would be nice, however, to collect what other people in philosophy tend to say about what they work on. Anyone care to share?

I've heard Nat say that he works on thoughts. On figuring out how to count thoughts.

I've heard Nat say that he works on thoughts. On figuring out how to count thoughts.

Thursday, November 03, 2005

Comrade In Arms

"Reality is that which, when you don't believe in it, doesn't go away."

Peter Viereck

From The New Yorker, October 24, 2005, p. 47

Peter Viereck

From The New Yorker, October 24, 2005, p. 47

Discussion of My New Brand of Moral Anti-Realism

Apparently, Nat is no longer the only reader of my blog. I guess that's a good thing. Yesterday, I received the following email from Daniel G. about my new brand of moral anti-realism:

"So, I read your blog. I think your idea about distinguishing moral from other facts is interesting. There's more than a good chance that I'm not totally getting your idea, but here are some thoughts that came to mind.

"Surely you want in a situation where someone comes to appreciate some moral fact for that fact to be part of the cause of the person *coming* to believe that fact. If so, then it looks like the moral fact is causally efficacious in a way not dissimilar to the rock - just as the rock is part of the story of how someone who denied that there is a rock comes to believe there is rock, so too with the case of someone who comes to see that such and such is the case morally. What seems important is that the rock can causally interact with a person without that person coming to have any belief about the rock, whereas the same does not appear to be true in the case of moral facts (though it is probably too limiting to restrict the kind of effect the fact can have to domain of belief only). My point is simply that you don't want it to be the case that someone must already have beliefs about the moral fact in order for that fact to be causally efficacious, otherwise it looks like the fact itself must be left out of an explanation of how someone comes to believe the fact. Also - I'm wondering how this idea is different from the kind of stuff McDowell and Wiggins have to say about secondary qualities. In this case too, it seems that the thing in question cannot be causally efficacious without reference to the subject who effected. But (and I take it this is McDowell's and Wiggins' point) this doesn't impugn the idea that the things doing the effecting are as real as we want them to be. I'm not saying that you're denying this. I'm just not sure that you've really switched camps so much as renamed something. But maybe not."

Here's the response I sent back to him:

Two points:

(1) McDowell and Wiggins don't have a substantive story about what distinguishes secondary qualities from primary qualities, so their invocation of secondary qualities as a model for what's distinctive about moral facts (and other "subject involving" facts) is empty. If you look at what they say, you'll find plenty of hand waving about the constitutive role our subjectivity plays in the make-up of moral facts, but this ceases to be a means to distinguish moral from other facts when you find out that they say all the same things about non-moral facts as well. (To be thorough: McDowell does make one proposal for distinguishing moral judgments: namely, at times he suggests that he accepts a version of judgment internalism--the view that sincerely making a moral judgment is necessarily connected up with being motivated to act. But on any serious construal of his comments on this topic, the specific formulation of judgment internalism he proposes is straightforwardly false. Michael Smith's criticisms of McDowell in this regard are definitive. On a less than fully serious construal of his comments, it is possible to water them down enough so that some form or another of judgment internalism turns out to be true of any kind of judgment. But then invoking judgment internalism ceases to be a means of distinguishing moral judgments and we're back where we started from.) And when it turns out that they offer no non-circular account of the constitutive role our subjectivity plays (in either case), my interest really starts to wane. At the end of the day, it's somehow supposed to be a quietist platitude that the constitution of the world depends on us! (If that's not global anti-realism, or idealism, I don't know what is. Yes, I've heard of Kant. And yes, I'm familiar with a way of reading Kant such that his transcendental idealism turns out to be just what McDowell's defending. But the tendency to waffle between talking about the constitutive dependence of the world on us and talking about how anti-realism is an illusion still strikes me as irresolute.)

The crux of my argument is that there is an important difference between the rationality of being consoled by the existence of non-moral, natural facts, and the irrationality of being consoled by the existence of moral facts. And I have a substative way of accounting for this difference: the reason it's rational to be consoled by the one but not the other is because the one is causally efficacious independently of what anyone believes about it. I think this suffices to separate my camp from theirs. (It's not essential to me that I be in some other camp. But, as far as I can tell, their camp's account of what's distinctive about moral facts is empty. And I hope that's not true of my account as well.)

(2) I don't know if your worry about the causal efficacy of moral facts poses a problem for my account. At worst, I need to qualify what I say (I just need there to be some dissimilarity or another in the area I'm pointing to, in spite of all the similarities--which I'm more than happy to grant), but I don't know if I even need to do that. In the case you imagine, I assume that someone else teaches you about the moral facts, and they do so by training you adhere to them even when you are not already aware of them yourself. (Think about Burnyeat's "Aristotle on Learning to be Good".) So one need not invoke the causal efficacy of the moral facts themselves on you, the unbeliever. All one needs is the causal efficacy of the facts on the believer and his effect on you. (Remember my claim: realism about x = x is causally efficacious independently of what anyone believes about x.) But you're probably right to suggest that such cases of other people bringing one into the space of morals can't exhaust our access to this space or the causal efficacy of it. You've given me something to think about.

"So, I read your blog. I think your idea about distinguishing moral from other facts is interesting. There's more than a good chance that I'm not totally getting your idea, but here are some thoughts that came to mind.

"Surely you want in a situation where someone comes to appreciate some moral fact for that fact to be part of the cause of the person *coming* to believe that fact. If so, then it looks like the moral fact is causally efficacious in a way not dissimilar to the rock - just as the rock is part of the story of how someone who denied that there is a rock comes to believe there is rock, so too with the case of someone who comes to see that such and such is the case morally. What seems important is that the rock can causally interact with a person without that person coming to have any belief about the rock, whereas the same does not appear to be true in the case of moral facts (though it is probably too limiting to restrict the kind of effect the fact can have to domain of belief only). My point is simply that you don't want it to be the case that someone must already have beliefs about the moral fact in order for that fact to be causally efficacious, otherwise it looks like the fact itself must be left out of an explanation of how someone comes to believe the fact. Also - I'm wondering how this idea is different from the kind of stuff McDowell and Wiggins have to say about secondary qualities. In this case too, it seems that the thing in question cannot be causally efficacious without reference to the subject who effected. But (and I take it this is McDowell's and Wiggins' point) this doesn't impugn the idea that the things doing the effecting are as real as we want them to be. I'm not saying that you're denying this. I'm just not sure that you've really switched camps so much as renamed something. But maybe not."

Here's the response I sent back to him:

Two points:

(1) McDowell and Wiggins don't have a substantive story about what distinguishes secondary qualities from primary qualities, so their invocation of secondary qualities as a model for what's distinctive about moral facts (and other "subject involving" facts) is empty. If you look at what they say, you'll find plenty of hand waving about the constitutive role our subjectivity plays in the make-up of moral facts, but this ceases to be a means to distinguish moral from other facts when you find out that they say all the same things about non-moral facts as well. (To be thorough: McDowell does make one proposal for distinguishing moral judgments: namely, at times he suggests that he accepts a version of judgment internalism--the view that sincerely making a moral judgment is necessarily connected up with being motivated to act. But on any serious construal of his comments on this topic, the specific formulation of judgment internalism he proposes is straightforwardly false. Michael Smith's criticisms of McDowell in this regard are definitive. On a less than fully serious construal of his comments, it is possible to water them down enough so that some form or another of judgment internalism turns out to be true of any kind of judgment. But then invoking judgment internalism ceases to be a means of distinguishing moral judgments and we're back where we started from.) And when it turns out that they offer no non-circular account of the constitutive role our subjectivity plays (in either case), my interest really starts to wane. At the end of the day, it's somehow supposed to be a quietist platitude that the constitution of the world depends on us! (If that's not global anti-realism, or idealism, I don't know what is. Yes, I've heard of Kant. And yes, I'm familiar with a way of reading Kant such that his transcendental idealism turns out to be just what McDowell's defending. But the tendency to waffle between talking about the constitutive dependence of the world on us and talking about how anti-realism is an illusion still strikes me as irresolute.)

The crux of my argument is that there is an important difference between the rationality of being consoled by the existence of non-moral, natural facts, and the irrationality of being consoled by the existence of moral facts. And I have a substative way of accounting for this difference: the reason it's rational to be consoled by the one but not the other is because the one is causally efficacious independently of what anyone believes about it. I think this suffices to separate my camp from theirs. (It's not essential to me that I be in some other camp. But, as far as I can tell, their camp's account of what's distinctive about moral facts is empty. And I hope that's not true of my account as well.)

(2) I don't know if your worry about the causal efficacy of moral facts poses a problem for my account. At worst, I need to qualify what I say (I just need there to be some dissimilarity or another in the area I'm pointing to, in spite of all the similarities--which I'm more than happy to grant), but I don't know if I even need to do that. In the case you imagine, I assume that someone else teaches you about the moral facts, and they do so by training you adhere to them even when you are not already aware of them yourself. (Think about Burnyeat's "Aristotle on Learning to be Good".) So one need not invoke the causal efficacy of the moral facts themselves on you, the unbeliever. All one needs is the causal efficacy of the facts on the believer and his effect on you. (Remember my claim: realism about x = x is causally efficacious independently of what anyone believes about x.) But you're probably right to suggest that such cases of other people bringing one into the space of morals can't exhaust our access to this space or the causal efficacy of it. You've given me something to think about.