Wednesday, May 31, 2006

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Tuesday, May 09, 2006

Monday, May 08, 2006

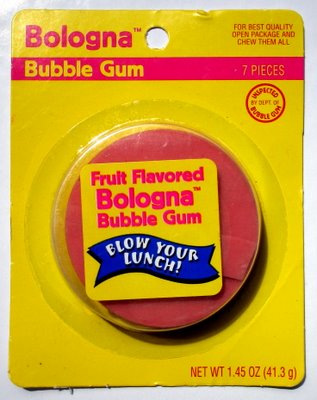

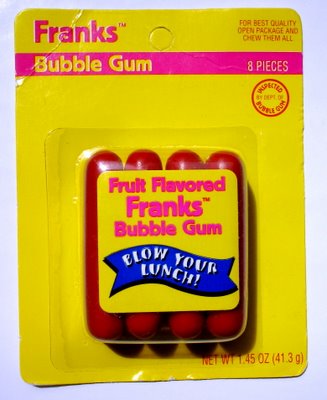

Album Cover Art, cont.

Although I should probably just add this new find to my previous post on album cover art, it's too good to be buried in my archives. So I'm posting it here.

Wednesday, May 03, 2006

Moral Relativism

I was on my old computer today, and I found an "essay" I wrote (for myself) on moral relativism about four years ago. Here it is:

In response to moral relativism, people usually do one of three things. Either they try and demonstrate how moral relativism contradicts itself when it tries to justify tolerance (or some other virtue); or they try and show how the relativist’s account of moral discourse is incompatible with something we all already think (e.g., that Nazism is absolutely wrong); or they argue that believing in moral relativism is morally corrupting. While I’m not opposed to these sorts of strategies for responding to moral relativism, I fear that they fail to really address the motivations that lead people to adopt relativistic accounts of moral discourse. And insofar as these motivations are left unaddressed, the appeal of moral relativism is left untouched. So I think it’s worthwhile to attempt to identify and address these motivations themselves, with the hope that showing how moral relativism doesn’t satisfy these motivations will more firmly dissuade people from it. (I should say that I think these motivations themselves are admirable. This is something the usual responses to relativism do not acknowledge.)

Here are three connected desires that I think often attract people to moral relativism:

(i) a desire to understand why there is widespread and persistent moral disagreement.

(ii) a desire to know how to best respond to this disagreement.

(iii) a desire to make sure that such a response respects all parties to this disagreement.

Unfortunately, I think moral relativism fails to satisfy any of these three desires.

(i) In trying to understand why there is widespread and persistent moral disagreement, moral relativism plausibly looks to other differences (than moral ones) that exist between the people who are parties to the disagreement to explain why they disagree in the deep and seemingly irresolvable ways they do. Thus, if one finds that Person A thinks genital mutilation is permissible but Person B thinks that genital mutilation is impermissible, one looks to other differences between Person A and Person B to explain why they disagree on this issue. A plausible place to look is to their cultures. Now, I will assume for now that there are easy ways to demarcate cultures: e.g., assume that one’s cultural identity is roughly fixed by one’s ethnic identity and upbringing (I don’t think this is a very accurate account of cultural identity, but at least it is conceivable that one could draw rough boundaries demarcating distinct cultures on these lines.) If and only if it then turned out that everyone (or, nearly everyone—i.e., excluding those not capable of genuinely holding beliefs) within Culture A thought that genital mutilation is permissible, then their upbringing and participation within Culture A would be at least a possible explanation for their belief that genital mutilation is wrong. (I say “possible” because upon examination it may turn out that there ís a better explanation; e.g., nearly everyone in white America today believes that Abraham Lincoln is dead, but the best explanation for this fact is not that they all share a cultural upbringing, but rather that it is true that he is dead and they have access to this truth through their education.) Unfortunately, it turns out that not everyone in Culture A does believe that genital mutilation is permissible (the truly unfortunate thing about this fact for the moral relativist is that it is in general true of all cultures; there simply are not any cultures within which everyone agrees on all moral questions). And as long as there is this failure of correlation between People A’s (the set of all Person As) moral beliefs and their participation in Culture A, participation in Culture A is not even a possible explanation for People A’s moral beliefs. Now, the obvious thing for the moral relativist to say at this point is that my way of demarcating cultures is too crude, that it fails to genuinely connect up with the differences in upbringing that have led to the differences in moral beliefs that underlie the widespread and persistent moral disagreements that there are. I agree that my demarcation of cultures is crude; what I disagree with is the moral relativist’s assumption that there is any non-circular way of specifying a person’s culture (in the sense the moral relativist is interested in) in order use differences in culture to explain differences in moral beliefs, without utilizing their current moral beliefs as a guideline. (Try and do it.) And, if differences in moral beliefs must be referred to in order to demarcate the differences in culture, then differences in culture cannot explain the differences in moral beliefs because it is simply tautological that differences in culture will result in differences in moral beliefs (because it is differences in moral beliefs that weíre going on in specifying the relevant differences in cultures). In conclusion: desire (i) is a noble one, but, unfortunately, it is not satisfied by the moral relativist’s pseudo-explanation. We are still in need of a genuine explanation for the widespread and persistent character of moral disagreement.

(ii) Relativism’s response to moral disagreement is to explain it away. More specifically, relativism’s response to moral “disagreement” is to claim that it really is just misunderstanding, since the moral beliefs that are in apparent conflict in these “disagreements” are, in fact, each appropriate in their own spheres. And since “disagreement” really is just misunderstanding, the only recommendation the relativist can make with regard to this “disagreement” is that we all leave everyone to themselves and not interfere with their lives by misapplying our moral concepts (which only apply to us) to them. Obviously, for this recommendation to make sense, it must provide a way of demarcating distinct moral spheres, in order to distinguish between where our concepts apply and where they don’t. And the problem, once again, is in demarcating these distinct moral spheres. Legal or national boundaries aren’t a viable option, for two connected reasons: first, moral questions aren’t legal questions (e.g., it is possible to ask whether a law is a morally good law and argue that it should be revised on the grounds that it isn’t a morally good law), and, second, people within a nation (or other legal entity) can find themselves morally distant from each other in the sense that there may be genuine failures of mutual understanding between them (think of some the moral disagreements that have taken place in the British Empire, for instance). But once we start demarcating distinct moral spheres on extra-legal grounds, relativism’s ability to guide us in our interactions with others quickly dissolves into a bland injunction to simply let others do whatever they would like, to themselves and you, regardless of what you think. Say that we decide that Catholics and Hindus inhabit distinct moral spheres (a not implausible suggestion). Now imagine a case in which a Catholic, for whom the treatment of animals is not a moral issue, proceeds to systematically torture the cows he keeps on his dairy farm. What is a Hindu to do? For the moral relativist, it does not make any sense to ask this question, because the actions of the Catholic are simply within his own moral sphere and therefore out of the reach of the Hindu’s moral understanding and judgment. If you think such a question so such as makes sense, you haven’t yet fully grasped the point of moral relativism. Notice that we haven’t yet attempted the task of trying to specify how, exactly, a moral sphere’s scope is to be demarcated. How about in physical terms, say on geographic lines (which need not be aligned with national or legal boundaries)? What, then, happens when an inhabitant of one moral sphere passes through a different moral sphere? Does he then become bound by their moral code, even though he doesn’t understand it and they don’t understand his? That answer seems to flatly contradict the grounds upon which the moral relativist argued that some moral disagreements, namely those in which people find themselves morally unintelligible to one another, should be opted out of because it doesn’t make sense and is therefore wrong (this moral judgment, that it is always wrong for the inhabitants of one moral sphere to pass judgment on the inhabitants of another, is the contradiction internal to moral relativism that is most frequently focused upon, but it is not what I’m interested in focusing on here) to apply your moral concepts in their moral sphere. But if we demarcate a moral sphere’s scope of applicability on whether or not groups are morally intelligible to one another, cross-sphere judgments are going to be legitimated in the cases in which the inhabitants of one moral sphere are able to come to an understanding of another, a conclusion which the moral relativist wants to avoid at all costs. Of course, the moral relativist could simply stipulate that there has never been, and could never be, a case of an inhabitant of one moral sphere coming to understand the moral life of an inhabitant of a different moral sphere; but the truth of such a stipulation seems rather far-fetched. Now imagine a third religious group, who inhabits its own moral sphere. They think that all the cows in the world are theirs, given to them by God for them to torture at will. Suppose this third religious group steals both the Catholic’s and the Hindu’s cows and tortures them. For the relativist, once again there’s no moral question of what to do. (Of course there is a legal question, but we’re interested solely in the moral question; and we may wonder what can ground the legal judgment that theft is wrong if we accept moral relativism.) The relativist is simply committed to saying, “If you inhabit a distinct moral sphere from me, feel free to do what you like with me and my possessions. I may protest that what you’re doing is illegal, but it surely isn’t—and cannot be—morally wrong.” And once we free up the criteria for demarcating distinct moral spheres, in an effort not to overlook local failures of moral intelligibility (say between different sects of Protestantism, or individuals within a sect with different interpretations of the Bible), we’ll quickly be left with a situation in which everyone may well inhabit a distinct moral sphere of their own and everyone is therefore free to do what they will with others; except, of course, the resolute moral relativist who refuses to pass judgment on those whose moral concepts are different from his own. This paragraph has quickly become absurd, but I hope the point has been made that moral relativism simply doesn’t provide any useful guidance with regard to the question of how one should respond to moral disagreement. What motivates this question is a genuine desire not to misconstrue the moral lives of others by simply blindly applying one’s own moral concepts to their lives with no concern for how these others understand themselves and what they’re doing. This is a noble desire and one that should be respected. But treating all others as in principle morally distant from one out of a fear that one might, on the basis of a concern to do good, actually come to harm them through the moral advice one offers them, isn’t a way of respecting this desire. It’s a way of evading it, by simply opting out of addressing the difficult problem (of what to do in response to moral disagreement) that originally provoked it. A concern for others—that they not be mistreated—is what originally provoked (ii), but letting others simply do what they will (the moral relativist’s recommendation) is not a form of concern. It’s a form of neglect and avoidance.

(iii) Desire (iii), like the first two, is also a noble one. One way to reformulate it is to say that respecting others is of paramount importance. (Notice once again that a moral judgment that applies to everyone is being made here: respecting others isn’t something we should only do to ourselves—whatever that means—it is something we should to others, all others.) The point is simply that something is really wrong with not letting others decide for themselves how they’re to understand themselves and what they’re to do with their lives (this is a point Kant is enormously interested in articulating and defending). Respect for others demands that we not force them to bow to our interests. I think this is all deeply true. What I also think is true, however, is that moral relativism (a) is completely incapable of defending this truth, insofar as it abhors moral judgments that apply to those outside of one’s own moral sphere and (b) is missing out on what respect for others actually demands of us. Moral relativism’s incapacity in regards to (a) seems rather straightforward, so I will focus here on (b). Imagine that you and I inhabit distinct moral spheres (however that is to be cashed out). I think nothing is better than spending all of my free time (which I have quite a lot of) sunbathing. I really like to sunbathe. All that is required for moral relativism’s account of “respect” (which just amounts to letting others do what they will) to be false is for there to be some justifiable point to your engaging in a conversation with me about whether or not spending all of my time sunbathing is good. Who’s to judge that sunbathing is or is not a good thing? Well, the short answer is “we are, in conversation with one another”. Of course, there will surely be times in that conversation in which we disagree and the burden of justifying our respective moral beliefs about what is and is not good falls upon us as individuals. But all that is required for moral relativism to be false is for there to be a form of interaction (call it moral conversation) in which you are trying to change my moral beliefs (at the same time that you’re submitting your own to my critical scrutiny, and therefore opening yourself up to the possibility to that I might lead you to change your moral beliefs by my criticisms of them) solely by offering me reasons that I can come to see as moving while at the same time in no way forcing or coercing me to change my beliefs. If such a form of interaction is so much as a possibility, moral relativism is false. More to the point, however, is the question of what respect for others demands of us. In the case imagined above, I honestly think, and hope, that your respect for me and my life would lead you to try and argue with me about whether or not spending all of my time sunbathing is a good thing. On the moral relativist’s understanding of ”respect’, however, “respect” demands that you say nothing to me about my sunbathing, simply because I inhabit a different moral sphere from you. I, for one, simply cannot see how this is a form of respect. It seems almost like a form of contempt, insofar as your refusal to engage in conversation with me on this topic assumes that I am incapable of understanding and discussing the merits of what you think speaks in favor of my not spending all my time sunbathing. But I don’t think that contempt really accurately characterizes the moral relativist’s understanding of ”respect”. Disregard is probably the most accurate characterization and I, for one, don’t think disregard for others is a good thing that’s to be recommended (although I also recognize that always having regard for others places demands upon us that we may not be able to live up to; I just don’t think we should respond to these demands by resting content with the moral relativist’s claim that disregard for others distant from us is across the board justified; in other words, I am genuinely troubled by the demands regard for others places upon me because I think these demands are real).

In response to moral relativism, people usually do one of three things. Either they try and demonstrate how moral relativism contradicts itself when it tries to justify tolerance (or some other virtue); or they try and show how the relativist’s account of moral discourse is incompatible with something we all already think (e.g., that Nazism is absolutely wrong); or they argue that believing in moral relativism is morally corrupting. While I’m not opposed to these sorts of strategies for responding to moral relativism, I fear that they fail to really address the motivations that lead people to adopt relativistic accounts of moral discourse. And insofar as these motivations are left unaddressed, the appeal of moral relativism is left untouched. So I think it’s worthwhile to attempt to identify and address these motivations themselves, with the hope that showing how moral relativism doesn’t satisfy these motivations will more firmly dissuade people from it. (I should say that I think these motivations themselves are admirable. This is something the usual responses to relativism do not acknowledge.)

Here are three connected desires that I think often attract people to moral relativism:

(i) a desire to understand why there is widespread and persistent moral disagreement.

(ii) a desire to know how to best respond to this disagreement.

(iii) a desire to make sure that such a response respects all parties to this disagreement.

Unfortunately, I think moral relativism fails to satisfy any of these three desires.

(i) In trying to understand why there is widespread and persistent moral disagreement, moral relativism plausibly looks to other differences (than moral ones) that exist between the people who are parties to the disagreement to explain why they disagree in the deep and seemingly irresolvable ways they do. Thus, if one finds that Person A thinks genital mutilation is permissible but Person B thinks that genital mutilation is impermissible, one looks to other differences between Person A and Person B to explain why they disagree on this issue. A plausible place to look is to their cultures. Now, I will assume for now that there are easy ways to demarcate cultures: e.g., assume that one’s cultural identity is roughly fixed by one’s ethnic identity and upbringing (I don’t think this is a very accurate account of cultural identity, but at least it is conceivable that one could draw rough boundaries demarcating distinct cultures on these lines.) If and only if it then turned out that everyone (or, nearly everyone—i.e., excluding those not capable of genuinely holding beliefs) within Culture A thought that genital mutilation is permissible, then their upbringing and participation within Culture A would be at least a possible explanation for their belief that genital mutilation is wrong. (I say “possible” because upon examination it may turn out that there ís a better explanation; e.g., nearly everyone in white America today believes that Abraham Lincoln is dead, but the best explanation for this fact is not that they all share a cultural upbringing, but rather that it is true that he is dead and they have access to this truth through their education.) Unfortunately, it turns out that not everyone in Culture A does believe that genital mutilation is permissible (the truly unfortunate thing about this fact for the moral relativist is that it is in general true of all cultures; there simply are not any cultures within which everyone agrees on all moral questions). And as long as there is this failure of correlation between People A’s (the set of all Person As) moral beliefs and their participation in Culture A, participation in Culture A is not even a possible explanation for People A’s moral beliefs. Now, the obvious thing for the moral relativist to say at this point is that my way of demarcating cultures is too crude, that it fails to genuinely connect up with the differences in upbringing that have led to the differences in moral beliefs that underlie the widespread and persistent moral disagreements that there are. I agree that my demarcation of cultures is crude; what I disagree with is the moral relativist’s assumption that there is any non-circular way of specifying a person’s culture (in the sense the moral relativist is interested in) in order use differences in culture to explain differences in moral beliefs, without utilizing their current moral beliefs as a guideline. (Try and do it.) And, if differences in moral beliefs must be referred to in order to demarcate the differences in culture, then differences in culture cannot explain the differences in moral beliefs because it is simply tautological that differences in culture will result in differences in moral beliefs (because it is differences in moral beliefs that weíre going on in specifying the relevant differences in cultures). In conclusion: desire (i) is a noble one, but, unfortunately, it is not satisfied by the moral relativist’s pseudo-explanation. We are still in need of a genuine explanation for the widespread and persistent character of moral disagreement.

(ii) Relativism’s response to moral disagreement is to explain it away. More specifically, relativism’s response to moral “disagreement” is to claim that it really is just misunderstanding, since the moral beliefs that are in apparent conflict in these “disagreements” are, in fact, each appropriate in their own spheres. And since “disagreement” really is just misunderstanding, the only recommendation the relativist can make with regard to this “disagreement” is that we all leave everyone to themselves and not interfere with their lives by misapplying our moral concepts (which only apply to us) to them. Obviously, for this recommendation to make sense, it must provide a way of demarcating distinct moral spheres, in order to distinguish between where our concepts apply and where they don’t. And the problem, once again, is in demarcating these distinct moral spheres. Legal or national boundaries aren’t a viable option, for two connected reasons: first, moral questions aren’t legal questions (e.g., it is possible to ask whether a law is a morally good law and argue that it should be revised on the grounds that it isn’t a morally good law), and, second, people within a nation (or other legal entity) can find themselves morally distant from each other in the sense that there may be genuine failures of mutual understanding between them (think of some the moral disagreements that have taken place in the British Empire, for instance). But once we start demarcating distinct moral spheres on extra-legal grounds, relativism’s ability to guide us in our interactions with others quickly dissolves into a bland injunction to simply let others do whatever they would like, to themselves and you, regardless of what you think. Say that we decide that Catholics and Hindus inhabit distinct moral spheres (a not implausible suggestion). Now imagine a case in which a Catholic, for whom the treatment of animals is not a moral issue, proceeds to systematically torture the cows he keeps on his dairy farm. What is a Hindu to do? For the moral relativist, it does not make any sense to ask this question, because the actions of the Catholic are simply within his own moral sphere and therefore out of the reach of the Hindu’s moral understanding and judgment. If you think such a question so such as makes sense, you haven’t yet fully grasped the point of moral relativism. Notice that we haven’t yet attempted the task of trying to specify how, exactly, a moral sphere’s scope is to be demarcated. How about in physical terms, say on geographic lines (which need not be aligned with national or legal boundaries)? What, then, happens when an inhabitant of one moral sphere passes through a different moral sphere? Does he then become bound by their moral code, even though he doesn’t understand it and they don’t understand his? That answer seems to flatly contradict the grounds upon which the moral relativist argued that some moral disagreements, namely those in which people find themselves morally unintelligible to one another, should be opted out of because it doesn’t make sense and is therefore wrong (this moral judgment, that it is always wrong for the inhabitants of one moral sphere to pass judgment on the inhabitants of another, is the contradiction internal to moral relativism that is most frequently focused upon, but it is not what I’m interested in focusing on here) to apply your moral concepts in their moral sphere. But if we demarcate a moral sphere’s scope of applicability on whether or not groups are morally intelligible to one another, cross-sphere judgments are going to be legitimated in the cases in which the inhabitants of one moral sphere are able to come to an understanding of another, a conclusion which the moral relativist wants to avoid at all costs. Of course, the moral relativist could simply stipulate that there has never been, and could never be, a case of an inhabitant of one moral sphere coming to understand the moral life of an inhabitant of a different moral sphere; but the truth of such a stipulation seems rather far-fetched. Now imagine a third religious group, who inhabits its own moral sphere. They think that all the cows in the world are theirs, given to them by God for them to torture at will. Suppose this third religious group steals both the Catholic’s and the Hindu’s cows and tortures them. For the relativist, once again there’s no moral question of what to do. (Of course there is a legal question, but we’re interested solely in the moral question; and we may wonder what can ground the legal judgment that theft is wrong if we accept moral relativism.) The relativist is simply committed to saying, “If you inhabit a distinct moral sphere from me, feel free to do what you like with me and my possessions. I may protest that what you’re doing is illegal, but it surely isn’t—and cannot be—morally wrong.” And once we free up the criteria for demarcating distinct moral spheres, in an effort not to overlook local failures of moral intelligibility (say between different sects of Protestantism, or individuals within a sect with different interpretations of the Bible), we’ll quickly be left with a situation in which everyone may well inhabit a distinct moral sphere of their own and everyone is therefore free to do what they will with others; except, of course, the resolute moral relativist who refuses to pass judgment on those whose moral concepts are different from his own. This paragraph has quickly become absurd, but I hope the point has been made that moral relativism simply doesn’t provide any useful guidance with regard to the question of how one should respond to moral disagreement. What motivates this question is a genuine desire not to misconstrue the moral lives of others by simply blindly applying one’s own moral concepts to their lives with no concern for how these others understand themselves and what they’re doing. This is a noble desire and one that should be respected. But treating all others as in principle morally distant from one out of a fear that one might, on the basis of a concern to do good, actually come to harm them through the moral advice one offers them, isn’t a way of respecting this desire. It’s a way of evading it, by simply opting out of addressing the difficult problem (of what to do in response to moral disagreement) that originally provoked it. A concern for others—that they not be mistreated—is what originally provoked (ii), but letting others simply do what they will (the moral relativist’s recommendation) is not a form of concern. It’s a form of neglect and avoidance.

(iii) Desire (iii), like the first two, is also a noble one. One way to reformulate it is to say that respecting others is of paramount importance. (Notice once again that a moral judgment that applies to everyone is being made here: respecting others isn’t something we should only do to ourselves—whatever that means—it is something we should to others, all others.) The point is simply that something is really wrong with not letting others decide for themselves how they’re to understand themselves and what they’re to do with their lives (this is a point Kant is enormously interested in articulating and defending). Respect for others demands that we not force them to bow to our interests. I think this is all deeply true. What I also think is true, however, is that moral relativism (a) is completely incapable of defending this truth, insofar as it abhors moral judgments that apply to those outside of one’s own moral sphere and (b) is missing out on what respect for others actually demands of us. Moral relativism’s incapacity in regards to (a) seems rather straightforward, so I will focus here on (b). Imagine that you and I inhabit distinct moral spheres (however that is to be cashed out). I think nothing is better than spending all of my free time (which I have quite a lot of) sunbathing. I really like to sunbathe. All that is required for moral relativism’s account of “respect” (which just amounts to letting others do what they will) to be false is for there to be some justifiable point to your engaging in a conversation with me about whether or not spending all of my time sunbathing is good. Who’s to judge that sunbathing is or is not a good thing? Well, the short answer is “we are, in conversation with one another”. Of course, there will surely be times in that conversation in which we disagree and the burden of justifying our respective moral beliefs about what is and is not good falls upon us as individuals. But all that is required for moral relativism to be false is for there to be a form of interaction (call it moral conversation) in which you are trying to change my moral beliefs (at the same time that you’re submitting your own to my critical scrutiny, and therefore opening yourself up to the possibility to that I might lead you to change your moral beliefs by my criticisms of them) solely by offering me reasons that I can come to see as moving while at the same time in no way forcing or coercing me to change my beliefs. If such a form of interaction is so much as a possibility, moral relativism is false. More to the point, however, is the question of what respect for others demands of us. In the case imagined above, I honestly think, and hope, that your respect for me and my life would lead you to try and argue with me about whether or not spending all of my time sunbathing is a good thing. On the moral relativist’s understanding of ”respect’, however, “respect” demands that you say nothing to me about my sunbathing, simply because I inhabit a different moral sphere from you. I, for one, simply cannot see how this is a form of respect. It seems almost like a form of contempt, insofar as your refusal to engage in conversation with me on this topic assumes that I am incapable of understanding and discussing the merits of what you think speaks in favor of my not spending all my time sunbathing. But I don’t think that contempt really accurately characterizes the moral relativist’s understanding of ”respect”. Disregard is probably the most accurate characterization and I, for one, don’t think disregard for others is a good thing that’s to be recommended (although I also recognize that always having regard for others places demands upon us that we may not be able to live up to; I just don’t think we should respond to these demands by resting content with the moral relativist’s claim that disregard for others distant from us is across the board justified; in other words, I am genuinely troubled by the demands regard for others places upon me because I think these demands are real).